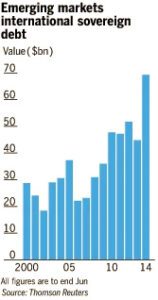

Keen observers of the African public sector finance and economic growth happenings will have noted the proliferation of the “trending” international bond issuances. Sovereign Debt issuance in the international financial markets is at all time highs. African sovereigns have latched onto the trend that has seen an explosion in sovereign debt by the bloc of emerging and frontier markets. International sovereign bond sales by emerging markets reached $69.47bn in the first six months of the year, a jump of 54 per cent on the same period in 2013. Emerging market economies are cannibalizing a temporal low rate / yield environment to secure debt at lower rates.

Ultra low rates in developed economies engendered by post financial crisis significantly unconventional monetary policy have eroded appeal for corresponding debt instruments. Investors are migrating to riskier assets while still offering attractive borrowing rates in turn incentivizing additional uptake of sovereign debt issuance in these markets.

Greece, formerly a cautionary tale on failed economic expedition, having sent the euro zone into a tailspin of economic crises, managed to attract orders amounting to 20 billion Euros in its first issue following its survival from the ledge.

Cyprus, is another example; participating in the debt markets merely 12 months after a banking crisis that required it to receive a 10 billion Euros Hail Mary from the IMF. In mid June this year, KENYA raised 2bn USD that was oversubscribed a respectable four times

AFRICA

Now, we examine how the African continent features in the context of the larger trend of emerging markets resorting to sourcing long term finance from the international debt markets. Investors true to their credo of searching for higher return on investment have been herded towards African sovereign debt. African economies provide a welcome alternative to low yielding developed market debt by offering higher premiums to investors on invested funds. The appeal of African debt is not tied to the higher premium it promises exclusively. Investors are buying into the African growth story.

The continent continues to outperform the developed world in terms of growth trajectory buoyed by commodity growth, and consumer driven economies catalyzed by a bulging middle class driving demand. Statistics are giving indication that the continent is on the up and up, and consideration is being awarded to recent natural resource discoveries of significant oil and natural gas deposits in pockets of Eastern Africa. This favors a robust economic outlook resulting from exploitation of these oil and gas reserves creating bankable upside potential. According to the African Development market, various barriers that were impeding African countries’ participation in international debt markets are in remission. In discussing the attractiveness of African debt they noted.

“…With the exception of South Africa, the African continent has long been neglected by global financial markets, largely due to perceived political risk, and weak economic performance. However, during the past decade, Africa has made substantial progress in improving political and economic governance. Africa now boasts robust average GDP growth, low debt ratios, abundant natural and human resources, among other potentialities. These factors have led to a reassessment of Africa’s risk configuration by global investors and opinion-makers in an environment characterized by uncertainty….”

The AfDB also is inclined towards encouraging sovereigns to take advantage of benign international financial market conditions (interest rate regimes and environment). Their contention is that this presents a golden opportunity for African nation states to plug the gap in funding the infrastructural requirements to ignite growth and transformation on the continent. There seems to be broad consensus on the mutually beneficial justification for African states to make use of the international debt markets and benefit from the pervading atmosphere of cheap money floating around post financial crisis circa 2008. The demand being seemingly insatiable, some sections will be ready to interpret this as the hawk eyed investor community explicitly endorsing the continent’s growth prospects.

Brief Chronology of African participation in International Debt Markets:

Gabon and Ghana first participated in international capital markets in 2007, while the Democratic Republic of Congo undertook a debt exchange in the same year. From 2011, there have been at least four issuances including the Zambian bond placement in September 2012, and Kenya in June 2014.Zambia, which has a credit rating of B+, raised US $750 million from a 10-year Eurobond at 5.6 per cent against the initial guidance of 5.9 per cent. The country planned to issue US $500 million, but this was upped in response to huge demand amounting to US $11.9 billion. The Zambian bond issue is considered cheaper relative to issuances by highly rated advanced economies such as Spain, rated BBB- (US $4.9 billion at an average 5.3 per cent). It also follows other debutant issuers – Namibia, Nigeria and Senegal – whose issuances were offered in 2011.In October 2011, Namibia, raised US $500 million on a 10-year bond with yield of 5.5 per cent.

Earlier, Nigeria and Senegal raised US $500 million each from international capital markets. Like the Zambian case, each of these issuances was oversubscribed; attesting to the growing attractiveness of the African debt market. Zambia’s hugely successful debut bond issuance has been touted by analysts as opening up opportunities in Africa’s bond debt market, particularly for the below-investment grade fast-growing economies.

RISK

The most important factor to consider before a transaction of this nature is undertaken is the significant market risk. Market risk, by definition, is the adverse nature of fluctuations in market prices of underlying financial market instruments against a market participant. The market is a capricious mistress who is wont to discard any instrument whose risks no longer represent their appetite to hold them. Political risk factors are always a concern where African nations are involved and market players’ (mis)perception of the risk of default on these instruments can drive up financing costs in an swift fashion, thereby lumping countries with skyrocketing debt servicing obligations. Such an occurrence in all likelihood can curtail growth and in worst case scenario, precipitate a large scale economic implosion. Recent history provides as a perfect example by the way of Argentina. The country amassed astronomical levels of debt from international debt markets primarily because the domestic market feared its own government’s capacity to be compelled to pay its debts.

Argentina has since run into a pickle. Rising Impending debt obligations gave rise to absorption of ever more debt, engendering a virtuous cycle of debt and perpetually deteriorating domestic economic situation, culminating in civic indiscipline and a host of other concomitant trappings of ailing debt riddled sovereigns. Argentina currently finds itself at the climax of a 12 year legal battle with one of its creditors; a Cyprus based American owned hedge fund NML capital, renowned Vulture capitalist, whom it refuses to pay up to 1 billion USD by trying to invoke sovereign immunity. It is however, finding it difficult to do, given that the bond was issued offshore (NYC). The American courts are unimpressed with the notion of the state enjoying the amenities of the American financial markets and choosing to voluntarily default when the hens come home to roost. The legalese surrounding this contest is highly complex but the purpose of highlighting Argentina’s current predicament was to draw attention to the implied risk that can assail a country that uses these instruments. Exposure to the vagaries of market dynamics in global financial markets can easily derail economies.

The IMF also struck a cautionary tone as far as African bond issuances are concerned. Even though it lauded the Africa rising narrative, and the positive sentiment as well as growth projections, it warned that prudent management of natural resources and juggling the foreign interests scrambling for a piece of the African pie is a delicate balancing act, that requires deft handling, and failing that, Africans might be forced to contend with rising debt obligations.

“…Governments should be attentive and they should be cautious about not overloading the countries with too much debt. That is additional financing, but that is an additional vulnerability…”

Christine Lagarde at a meeting with African Finance Ministers in Mozambique

Ms Lagarde warned that investors have started to demand higher interest rates for holding the debt of some African countries, a sign the market has become increasingly wary of rising fiscal deficits. When Zambia returned to the sovereign bond market earlier this year, it had to pay a yield of 8.625 per cent for a 10-year $1bn note, up from 5.63 per cent on its bond market debut in 2012.The IMF forecasts that fiscal deficits in sub-Saharan Africa will hit 3.3 per cent of the gross domestic product in 2014, a large swing from a surplus of 2.5 per cent in 2004. Investors are beginning to question whether they are receiving fair premiums for the risk they are undertaking by purchasing African Debt. A rise in U.S. Treasury yields earlier this year also led investors to take a second look at emerging-market credit, in general, and for some market participants to question whether investors in African debt are adequately compensated for risk.

“…A number of African Eurobonds were trading very tight to begin with. Nigeria\’s 2021 bond has traded at a spread to U.S. Treasurys as low as 210 basis points [2.1 percentage points]. For a BB- rated country, that\’s quite exceptional….” said Samir Gadio, emerging-markets analyst at Standard Bank.

That is a worry, given the growing pains in Africa. Ghana, which sold its first international dollar bond in 2007, is a case in point. The West African country showed a budget deficit last month that was 12.1% of gross domestic product —3% over target—because of higher spending and lower tax income. That is worryingly similar to when Argentina was in trouble, their budget deficits at 15% of GDP, fuelling concern that Ghana, former poster boy of the region, is headed alarmingly fast in the wrong direction and has fallen out of favor with its international admirers. Ghana is currently battling runaway inflation, approaching the region of 30%, its currency the Cedi, in free fall.

Regardless, however, consensus is that demand for African debt remains strong in the medium term, but it is important to note the following.

- The African continent is not a monolithic homogenous bloc, so local contexts and factors must be considered in understanding the unique risk elements for particular sovereigns.

- African states need to properly understand the significant risks associated with participating in the international debt market, some of which can be detrimental to economies’ long term survival.

- Implications for successful Bond issuance in international debt markets are consistent with prudent macroeconomic and public sector management, and maintaining a lid on fiscal deficits.

- The rush to mop up cheap money from the international debt markets should not overshadow the ultimate responsibility of countries to maintain manageable debt levels as a percentage of their GDP